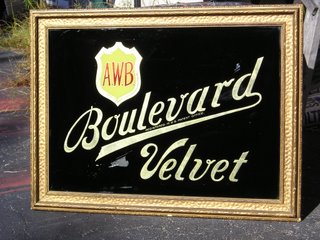

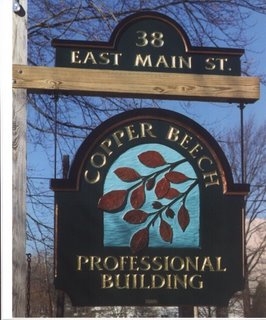

The official Finest Kind Sign website is now live, with several things still under construction, at www.finestkindsign.com Today I spent a couple of hour on the phone with Jeremy Fennema, my webmaster at www.builditbuyit.com learning how to edit pages. Okay, so it sounds easy on the phone... suffice to say I have great respect for the skills involved in website design. Anyway, there are now more photos up and some neat stuff to see, coming from the archives of the last 18 years in this business. Its interesting - to me at least - to see how my designs have evolved over the years; how some have aged well and others look dated or less than what I would want to do now.

The big change has come from computer-assisted design. It's so easy now to fine-tune a design, adjust copy size or spacing or try different letterstyles. In the past when everything was drawn and patterned by hand, it was a lot of work to make even small changes, and admittedly there were days when time constraints and exhaustion allowed things to be done less than perfectly. One bugbear that always pestered me, back then, was centering. I have a hell of a time looking and judging a center by eye - I'm always off, just a bit, whereas for lines being level and parallel I can spot an eighth-inch variation over a six-foot length. When an entire sign is patterned by hand and one line is an inch off center, you either re-do the pattern or figure out "shortcuts" - like pouncing (which means transfering the pattern to the signboard with powder) the whole sign, wiping away the off-center part, moving the pattern to re-center the offending bit, then pouncing just that line again. If it sounds half as effing tedious as it is, I've done an adequate job describing it. Now, I fine-tune the design on screen (where the justify feature is my friend) and the plotter perforates a perfect pattern (say that three times fast!) This saves me a hell of a lot of time and labor, allowing me to let machines do the tedious work and letting me do the painting.

Still, I can't over emphasize the value of those years of doing everything by hand. Traditional methods force you to pay attention to details and to have an intimate acquaintance with letterforms like nothing else. No computer program will ever replace or substitute for those skills, even if after all these years I still can't see center.